Isometric Scala Game Engine

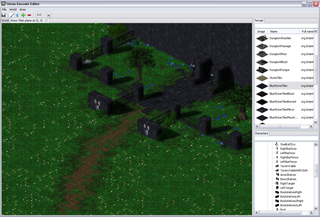

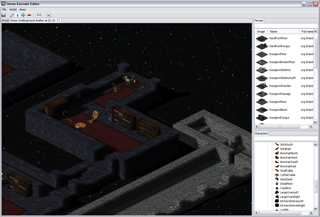

Last year I’ve spent some time working on an isometric RPG-like game engine written in Scala. Knowing that I wouldn’t be able to write a game in my free time alone, I’ve decided to limit myself to a level editor rather than a complete game.

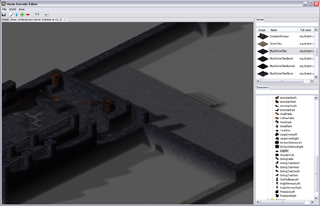

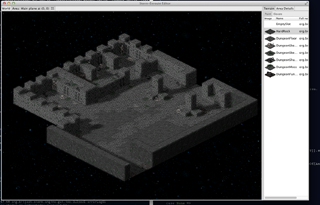

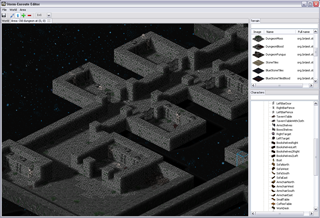

One of the classic arguments people have against Java when it comes to coding games, and along that line Scala too, is bad performance – I was eager to find out to which extent this is really a problem. While what I wrote is not a Crysis engine and this is hardly an extensive analysis, it seems to me that with a little knowledge of what certain higher abstractions translate into, you can write fairly efficient game engine code when it comes to Baldur’s Gate/Diablo style RPG-like engines. The level editor is written largely in Scala, relying mainly on SWT and OpenGL libraries (specifically, the JOGL bindings), with a little bit of shaders written using GLSL. There are some screenshots below.

</img> </img>

|

</img> </img>

|

</img> </img>

|

</img> </img>

|

|

|

In case it’s not obvious from the screenshots – I am a huge fan of sprites. You can’t blame me – I grew up on them. In fact, I am one of those guys who believe that stunning graphics is not an essential ingredient of a quality game or a prerequisite for good gameplay. In fact, I spent a lot of time playing games like ADOM. A bit of nice visual effects is fine, but the game should not be just about those. Also, sprites often allow a higher level of detail, which is neater to the eye. This higher level of detail comes from the fact that they are pre-rendered, potentially using models with a higher polygon count, special effects like hair and fur, as well as material models that allow defining surface properties such as reflection, bump and transparency. Although GPUs are getting faster every day, usually it is more expensive to compute these on-the-fly. But, I will get back to this at the end of the post.

However, this blog post is not meant to be a philosophical debate – rather, I want to share some of my experience of implementing in Scala. In the rest of this blog post I describe the details of the engine implementation. I will go through the rendering process, some of the advantages of Scala when it comes to conciseness and pretty code (particularly when dealing with OpenGL) and creating sprites using 3dsMAX with some custom MaxScript functionality for outputing data for 3d objects. Finally, I share some thoughts on what I would do differently, what some of the goals were and possible future work if my free time allows it.

The rendering procedure

As mentioned before, most of the game is sprite-based.

All sprites are rendered using 3ds MAX and then placed into appropriate positions by the

game engine at runtime to produce the entire image.

What are sprites?

In short, these are two-dimensional images integrated into a larger scene.

The scene is in this case what you see in the screenshots above.

A sprite is just a relatively small PNG image with transparent background that you can blend into the scene.

All sprites are rendered using 3ds MAX and then placed into appropriate positions by the

game engine at runtime to produce the entire image.

What are sprites?

In short, these are two-dimensional images integrated into a larger scene.

The scene is in this case what you see in the screenshots above.

A sprite is just a relatively small PNG image with transparent background that you can blend into the scene.

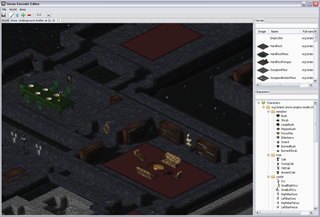

There are two basic types of sprites in this engine.

The first are terrain sprites and the second character sprites.

The fireplace shown on the right image is a character sprite – it is rendered above the terrain sprites.

The small rhomboid on the left with some grass on top is a terrain tile.

Terrain tiles cover the scene – other sprites are rendered to appear as if they are above them.

Terrain tiles are sprites that have a fixed size, whereas character sprites may have a different height

and may occupy several tiles.

There are two basic types of sprites in this engine.

The first are terrain sprites and the second character sprites.

The fireplace shown on the right image is a character sprite – it is rendered above the terrain sprites.

The small rhomboid on the left with some grass on top is a terrain tile.

Terrain tiles cover the scene – other sprites are rendered to appear as if they are above them.

Terrain tiles are sprites that have a fixed size, whereas character sprites may have a different height

and may occupy several tiles.

When it comes to fully 2D top-down perspectives it’s very easy to place sprites into the

scene – usually it amounts to passing through the image in the order in which sprites should appear

and blending them.

When it comes to fully 2D top-down perspectives it’s very easy to place sprites into the

scene – usually it amounts to passing through the image in the order in which sprites should appear

and blending them.

In the case of tile-based top-down perspective games, where different sprites occupy different tiles, this means having to loop

through the rows of tiles in the scene and through the tiles in each row.

However, when it comes to isometric tile-based engines where a sprite may occupy more than a single

tile, things get a bit more convoluted.

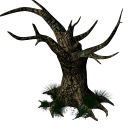

The chair on the left occupies a single tile (1x1 sprite),

but the oak tree on the right occupies four tiles (2x2 sprite)

and the fireplace shown earlier occupies three tiles (1x3 sprite).

The sprites can no longer be drawn going from one corner of the scene to another,

so two simple

In the case of tile-based top-down perspective games, where different sprites occupy different tiles, this means having to loop

through the rows of tiles in the scene and through the tiles in each row.

However, when it comes to isometric tile-based engines where a sprite may occupy more than a single

tile, things get a bit more convoluted.

The chair on the left occupies a single tile (1x1 sprite),

but the oak tree on the right occupies four tiles (2x2 sprite)

and the fireplace shown earlier occupies three tiles (1x3 sprite).

The sprites can no longer be drawn going from one corner of the scene to another,

so two simple for loops will not do.

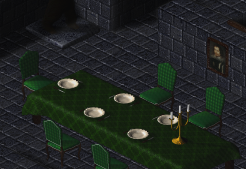

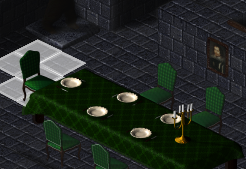

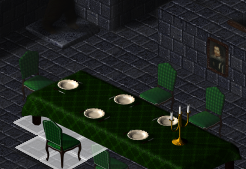

Lets focus on the following detail in one of the screenshots – a dining table with chairs around it.

The dining table is something like a 7x3 sprite and each chair is a 1x1 sprite.

If we render rows of tiles from the north-east going to south-west, and render tiles in each

row going from north-west to south-east, then the chair on the head of the table will be rendered

after the table, making it seems as if they overlap.

Consequently, if we render the rows from north-west to south-east, then the chairs in the middle

of the table will be drawn over it.

The dining table is something like a 7x3 sprite and each chair is a 1x1 sprite.

If we render rows of tiles from the north-east going to south-west, and render tiles in each

row going from north-west to south-east, then the chair on the head of the table will be rendered

after the table, making it seems as if they overlap.

Consequently, if we render the rows from north-west to south-east, then the chairs in the middle

of the table will be drawn over it.

The naive approach of sorting all the visible sprites in the scene (either by maintaining a binary search tree or sorting them just once before rendering) and then rendering them in that order won’t work either. The problem is that the sprites that occupy rectangular areas do not form a total order with respect to rendering (note that the more general problem of rendering sprites that occupy non-rectangular areas is not really solvable – in this case sprites could overlap). Instead, they form a partial order – given two sprites and their locations on the screen you can only tell which should be rendered first if they overlap. Otherwise, their relative rendering order depends on other sprites that are potentially between them. This means that binary search trees or an efficient comparison sort won’t help you. These approaches assume the existence of total order between the elements, without it the sprites would be spuriously rendered out of order.

Another complicating factor is that the terrain is not just one huge flat area – different terrain tiles can have different elevations. This design decision is meant to make the whole scene more realistic. Note, that the engine does not allow two tiles to be above each other, though, to keep things simpler.

After having shown the difficulties of rendering in an isometric tile-based scene, lets show how our engine copes with this.

First of all, notice that while a classic comparison sort requires the elements to form a total order, comparing all the elements of the scene mutually can yield a proper rendering order (this is precisely what efficient comparison sorts were designed to avoid by relying on the transitivity property of the total order).

We can compare each sprite X in the scene to each other sprite Y in the scene and store a dependency X->Y if Y should be rendered before X.

This forms a directed acyclic graph (we have to be careful how exactly we define dependencies between sprites to guarantee this acyclicity).

To render the sprite X we can then find all the sprites Y for which there is a dependency X->Y, and recursively render sprite Y if it has not been rendered yet – only after all the dependencies have been rendered can X be rendered itself.

Unfortunately, this also yields and

To render the sprite X we can then find all the sprites Y for which there is a dependency X->Y, and recursively render sprite Y if it has not been rendered yet – only after all the dependencies have been rendered can X be rendered itself.

Unfortunately, this also yields and O(n^2) asymptotic complexity when creating the dependency graph as the number of sprites n grows, which will typically happen as the screen resolution goes up.

However, it is straightforward to see that we do not need to look for a dependency between all the sprite pairs.

Most of the sprites have the property of being relatively small, so the sprites that they could overlap with should be somewhere in the immediate vicinity.

In the image on the right the tiles that could contain sprites that the chair could possibly overlap with are highlighted.

Note that we have to check only 7 tiles for objects instead of thousands of them.

In this case there are no objects “behind” the chair, so it has no dependencies.

On the image on the left we highlight the tiles the second chair depends on – in this case those tiles contain the dinner table, and the chair has a direct dependency on it.

The dinner table on the other hand has a dependency on the first chair, so there exists a transitive rendering dependency between the second and the first chair.

Once the dependency graph is fully created a simple for-loop can be used to render all the tiles and the sprites on the screen by checking if all the dependencies have been rendered and rendering them when required.

Note that in the worst case the complexity is still quadratic, but only if all the sprites have sizes proportionate to the size of the screen, and no sprites are that big.

On the image on the left we highlight the tiles the second chair depends on – in this case those tiles contain the dinner table, and the chair has a direct dependency on it.

The dinner table on the other hand has a dependency on the first chair, so there exists a transitive rendering dependency between the second and the first chair.

Once the dependency graph is fully created a simple for-loop can be used to render all the tiles and the sprites on the screen by checking if all the dependencies have been rendered and rendering them when required.

Note that in the worst case the complexity is still quadratic, but only if all the sprites have sizes proportionate to the size of the screen, and no sprites are that big.

Note that each sprite has multiple dependencies – this means we cannot tightly encode all the dependencies within a single object, because there is a variable number of them. We could use a dynamically growing array to store the dependencies, but then we have to dynamically reallocate the array and copy dependencies. We could use linked lists to avoid this, but allocating a node for each link increases the memory footprint, the amount of work and also creates a pressure on the garbage collector. Instead, we use something in between arrays and linked lists – an unrolled linked list. Instead of each node holding a single dependency, it holds several of them, in our case up to 32. Once a node is filled, an additional dependency node is allocated. We encode this as follows:

final class DepNode {

val deps = new Array[Int](32)

var sz = 0

var next: DepNode = null

var freeNext: DepNode = null

}

The deps array contains the dependencies for the current sprite encoded as tile coordinates, while the sz field denotes how many entries in the array deps should be considered – the array may not be full.

Adding a new dependency amounts to writing to the array and incrementing sz.

Once sz is equal to 32 we allocate a new DepNode object and assign it to next.

We will come back to describing what the freeNext field is used for.

To traverse all the dependencies, we have to traverse the deps array, and the next node recursively if it is non-null.

This way the unrolled linked list traversal performance can be made arbitrary close to that of a regular array traversal, and it has nice locality properties as well.

Interestingly, while this decreases the memory footprint on the JVM, the actual performance difference between unrolled linked lists and regular linked lists is not that big.

This is partly because the GC has to do approximately the same amount of work when collecting the unrolled linked list nodes as linked list nodes, and partly because each time an array for the unrolled linked list is allocated, it has to be cleared first.

Although object pooling on the JVM is generally not recommended, we can avoid these two costs in this case by maintaining a variant of a free list memory pool implementation.

We maintain a separate singly linked list of DepNode objects, linked together using the freeNext field.

To allocate a DepNode object we do the following:

var freeList: DepNode = initialPool()

def alloc(): DepNode = {

if (freeList == null) new DepNode()

else {

val depnode = freeList

if (depnode.next == null) {

freeList = depnode.freeNext

} else {

depnode.next.freeNext = depnode.freeNext

freeList = depnode.next

depnode.next = null

}

depnode.freeNext = null

depnode.sz = 0

depnode

}

}

Essentially, we create an object if there are no free objects left in the free list.

Otherwise, we return the first object on the free list.

If the first object had its next field set to null, then the free list head becomes the next object in the free list as denoted by the freeNext field.

Otherwise, the next node in the unrolled list that depnode was previously a part of becomes the head of the free list.

Once the frame is rendered, all the sprites in the scene have to have their dependency lists deallocated by calling dealloc.

Keeping a two-dimensional free list like this makes the deallocations really fast:

def dealloc(depnode: DepNode) {

depnode.freeNext = freeList

freeList = depnode

}

Not having a two-dimensional free list would require deallocating every unrolled linked list node by traversing the list, and O(n) operation for each list – although most sprites will not have many dependencies, this would still be slower.

Once all the sprites are rendered we end up with a nice-looking scene, although somewhat flat. Such a scene will be lacking depth – if you played Crusader in the 90s you’ll know what I’m talking about. To overcome this and add more realism, we do something untypical for most sprite-based engines – we employ shadow-mapping so that the objects cast shadows. Shadow-mapping is a technique that requires a 3D representation of the scene, which the sprites lack. In the next post in this series I will describe how we achieve shadow mapping.

comments powered by Disqus